The Hopi

The Hopi are an indigenous people inhabiting their ancestral lands, nearly 4,000 square miles of high arid terrain, in North Central Arizona.

Within this vast area, the main villages cling to three rocky mesas. The village of Orabi may be the oldest continuously inhabited community in this country. The Hopi people, as artists and crafts people, excel in a number of fields.

The residents of the First Mesa area are noted for their pottery, Second Mesa for coiled baskets, and Third Mesa for wicker plaques. The carving of tihus (dolls representing katsinas originally used as a means of education for the young) and silversmithing have traditionally been the realm of the men of all three mesas, however, in our generation a number of women have become very accomplished silversmiths.

The Sacred Hopi Calendar

The following is used with the permission of the Museum of Northern Arizona.

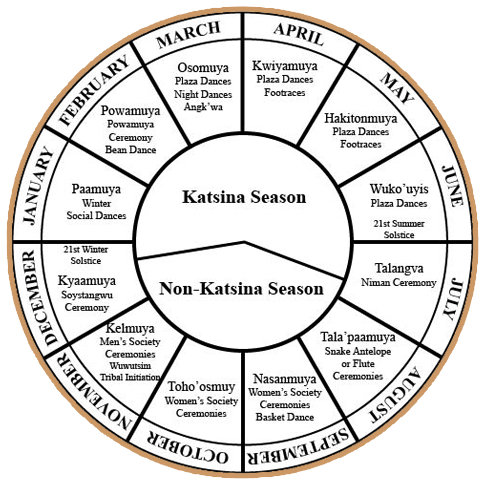

Hopi sacred time and space are marked by positions on the horizon where the sun rises and sets at summer and winter solstices. The solstice points in the southeast, where the sun rises at winter solstice (December 21st), and in the northwest, where the sun sets at the summer solstice (June 21st), are known as the sun's houses (Tawaki). The sun chief or priest of the Water (Patki) Clan is responsible for "sun watching" near the solstices. These observations form the basis for the Hopi Calendar within which the sacred ceremonies such as Katsina dances, Social Dances, and planting times occur.

A fundamental theme of the Hopi world view is that the universe is divided into two realms, the upper world of the living and the lower world of spirits. Events occur regularly between these two worlds in alternating cycles. For example, the sun moves between the upper world by day and the lower world by night. Likewise, it follows an alternating cycle through the year. When it is planting time (Spring) in the upper world, it is harvest time (Fall) in the lower world.

Similarly, there is a cycle for an individual: one is born, lives, dies and goes to the spirit realm-to be reborn as ancestor spirits, or Katsinam, as are the spirits of the animals and plants. As spirit beings, they act by carrying the prayers of the living to the deities, or by interceding with the forces of nature to promote that which sustains life in the upper world.